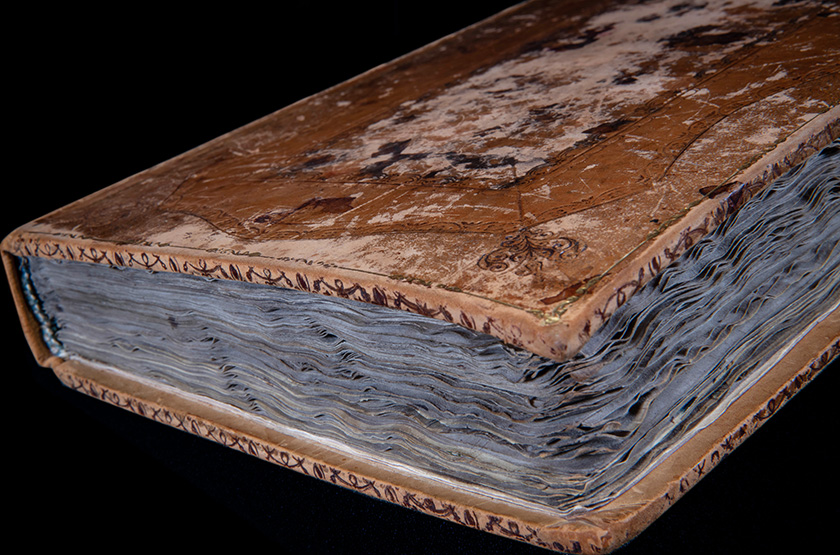

Photo: Gorm K. Gaare/National Library of Norway.

Magnus Lagabøte’s[1] Landslov[2] of 1274 was the first nationwide legal code in Europe that was actually used. It led to comprehensive societal reforms in Norway. With a lifespan of 400 years, this code of law is, alongside the Constitution of 1814, perhaps one of the two most important documents in Norwegian history.

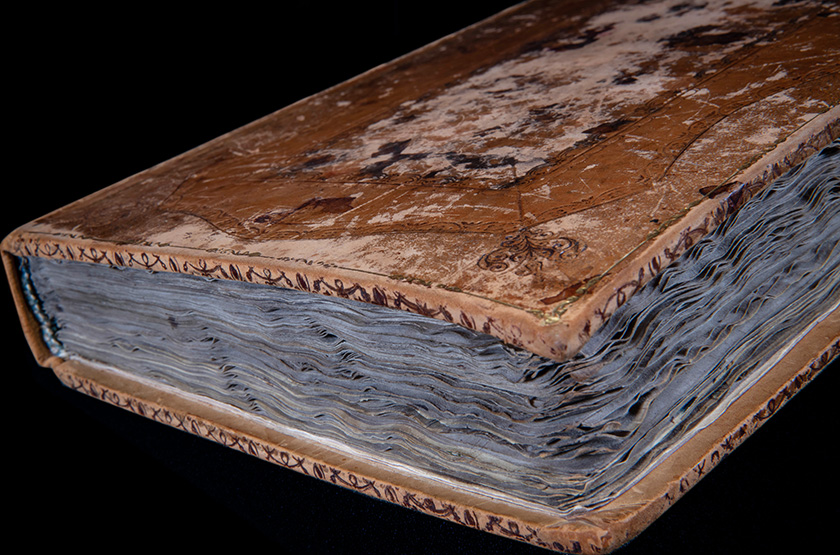

Magnus Lagabøte’s Landslov, photographed at the National Library of Norway for the exhibition Opplyst (“Illuminated”). Photo: Gorm K. Gaare/National Library of Norway.

The Landslov of 1274 is a major work in Norwegian and European history. It was formed at a time of great change across the continent. Since the latter half of the 11th Century, Europe had entered a more peaceful period, characterized by trade and the formation of towns and cities. The first universities were being established in Southern Europe. Peace, economic growth, and learning enabled rulers throughout Europe to engage in politics and state-building far more effectively and comprehensively than before.

At this time, the power of the state was growing ever stronger in Europe. In the Middle Ages, state power was markedly different to how we understand it today, divided as it was between the Church and the King. The Church conducted politics and regulated laws within the spiritual sphere. Anything that directly concerned God was legislated by the Church, and enforced in ecclesiastical courts by men of the church. The King, on the other hand, was responsible for secular politics and legislation.

The Church was a large, extensive, international organization, strengthened through communication, administration, learning and laws. Through this, it showed the way for how worldly rulers could govern their kingdoms. Gradually, these men enforced their rule through legislation rather than military might, replacing old traditions with new laws. Slowly but surely, Europe as we know it today began to take shape.

The developments taking place more widely across Europe also influenced Norway. The reign of King Olav III (or Olav the Peaceful) from 1067 to 1093 marked the end of the Viking era. He was the first Norwegian medieval king not to go to war. Instead, he built towns and expanded the country’s infrastructure. In 1153, a separate archbishopric was set up in Nidaros, present-day Trondheim, as a centre for learning and European ideas in Norway.

Even in the period of civil war between 1130 and 1240, the monarchy continued to develop its administration, and its ability to conduct politics. When King Håkon IV emerged victorious from a series of armed conflicts in the mid-13th Century, everything was in place for the building of Norway. Håkon IV was an important legislator, comparable perhaps to King Louis IX of France. But it was King Magnus VI (usually referred to as Magnus Lagabøte – Magnus the Lawmender) who was to become the most important legislator in Norwegian history. With the Landslov of 1274, he brought comprehensive reforms to Norwegian society. The code of law lasted for 400 years. Being Norwegian in the late Middle Ages was the same as having the Landslov as one’s legal code.

During the 13th Century, there were numerous European rulers who issued laws and even whole codes of law for cities, towns and regions. But the Landslov was at that time only the third nationwide code of law in the continent. The very first medieval nationwide legal code in Europe was Sicily’s Liber Augustalis[3], issued in 1231 by the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II. Following that were Las Siete Partidas for Castile (modern-day Spain) in 1265, and the Norwegian Landslov in 1274. In approximately 1350, Sweden – much inspired by the Landslov – also issued its own legal code.

After Las Siete Partidas, the Landslov was the second legal code in Europe during that time which regulated all aspects of medieval society. Work on Las Siete Partidas was known to King Magnus, since his sister, Kristin, had married Prince Philip of Castile in 1258. Perhaps it was this that persuaded King Magnus to follow suit, and to issue such a code of law for Norway.

In fact, the Landslov was the first European code of law that was actually used. Las Siete Partidas was a wonderfully learned body of legislation, but it was too extensive and complex to have any great influence on the everyday lives of the people. The Landslov, on the other hand, was deliberately designed to be so simple that it could be understood and used.

The Landslov is the most widely distributed Norwegian manuscript of the Middle Ages. It is probable that there was one for every 1150 inhabitants in Norway. This doesn’t imply that it was common to own a manuscript of the legal code; it took over 40 calfskins to make one code of law, meaning that only wealthy farmers, members of the aristocracy and pastors could afford to purchase one. Nevertheless, nearly all the preserved copies of the Lanslov are relatively simple and free of illustrations. This indicates that they were working manuscripts, made for practical use rather than to be exhibited as a status symbol.

The changes in Europe and Norway that were taking place during the 1200s called for social reforms and new legislation. There was a need for new rules in huge parts of society, from trade to the renting of farms. It was necessary for some areas, such as the penal code and the system of poor relief, to be completely changed. Put simply, the rules which had worked well from the Viking Age until the second half of the 11th Century were no longer sufficient as one moved further into the 12th Century. The Landslov was intended to guide Norway into the new society that was emerging throughout Europe.

King Magnus Lagabøte is Norwegian history’s most important legislator. Born in 1238, he reigned alongside his father, Håkon IV, from 1257 until the latter’s death in 1263, and then on his own until he himself died in 1280. Yet King Magnus was the king who wasn’t meant to be king. He had an elder brother, Håkon the Young, who was crowned King in 1239 when Magnus was only one year old. Since Håkon the Young also had a son, Sverre, Magnus was actually third in line for the throne.

Consequently, Magnus was not involved in politics while growing up. Instead, we know from the Scottish Lanercost Chronicle that he was educated by Franciscan monks in Bergen. They lived in the slum area of the city, where they looked after the neediest in society. As a prince, Magnus had his seat in court; through his education, he knew what the everyday life of the very poorest was like.

It is highly likely that the time King Magnus spent as a young man in Bergen, and the insight he gained into the full breadth of Norwegian society explains why the Landslov reformed the system of poor relief. Not only did the new legal code provide the poor with food and a roof over their heads, it also gave them the opportunity to escape poverty through agriculture or trade. The Landslov introduced rules for the renting of farms, mortgages and credit, purchase and sale, and the transport of commodities by ship.

In other words, the Landslov was a broad piece of societal regulation which covered all those who lived in Norway. The Landslov states explicitly that the King shall consider and make laws for both those with property and those without, not only in the present day, but for forthcoming generations. In short, the it applied to all the inhabitants of Norway, and it was the King’s duty to pay equal heed to those with the power to influence legislation, and those without.

It is unlikely that the Landslov was intended to apply for the Sami population in Norway. They had their own laws and rules. However, it appears that it was used by corrupt royal officials as an excuse to impose fines and other penalties on the Sami. This appears to have prompted the King of Sami, Martin, who is not known from other sources, to enter into an agreement in 1313 with King Magnus’s son, King Håkon V. This agreement gave the Sami 20 years to adapt to the Norwegian legislation that would apply to them, such as the marriage laws.

Because marriage law was another area in which the Landslov instituted major changes. For the first time, women were given the right of inheritance from their parents. The inspiration for this change probably stems from Denmark, and Queen Ingeborg, who had married King Magnus in 1261. Ingeborg was an active politician after Magnus’s death in 1280, and there is good reason to believe that she was also closely involved in the work on the Landslov.

Although women were still only accorded half the inheritance of their brothers, the new legislation meant that all women – both married and those who remained unwed – received capital from their parents. But unlike the rules in Denmark, the Landslov specified that women over the age of 20 were of legal age, and could make use of their own property as they wished.

King Magnus saw himself as a legislator in the tradition of King Olav II (often called Saint Olav or Olav the Holy), who is said to have issued a comprehensive set of laws, and – as such – was responsible for extensive societal change in 1024. However, what was new, strange, and controversial at the beginning of the 11th Century was far more generally acceptable when the Landslov was introduced in 1274. Not that the Landslov was uncontroversial. This becomes obvious when we study the variations between the numerous manuscripts that still remain.

With the Landslov being reproduced by hand, the scribes could sometimes make mistakes. Other times, writers would change the wording of the legal code on purpose since they found the contents too radical. One example of this is the right of retaliation. The Landslov abolished the right to avenge serious violations of the law, such as physical injury, theft, defamation and sexual relations with another man’s wife or female family member. Yet in almost half of the preserved Landslov manuscripts, the scribe has instead written in a general right of retaliation. There are also revealing variations relating to other evidently controversial societal reforms, such as the system of poor relief and the rights of women.

The Landslov was at the heart of King Magnus’s major legislative project; one which lasted throughout his reign, and culminated in the Landslov of 1274. The City Law[4] of 1276; a court and administrative law from the 1270s; and, finally, a code of law for Iceland called the Jónsbók. The Icelandic legal code, dispatched by ship in the spring of 1280, was the final chapter in King Magnus VI’s huge legislative project. He died on 9th May the same year.

Photo: Gorm K. Gaare/National Library of Norway.

The Landslov was commemorated in 2024 to mark the 750th anniversary of this historic document. In many ways, by creating a framework for the Norwegian state, the Landslov marked the end of the gradual changes that had taken place since the 11th Century. Today, much has changed, and Norway is completely different to what it was like in 1274. Yet legislation is still a vital means of putting policies into practice, and in this way governing society. Modern Norwegians retain great faith in the law, and compromise and consensus still retain high political status in the country. This is not simply because of the Landslov. But there is little doubt that it did play a significant role in a long and complex historical development.

This is a translation of a Norwegian article by Jørn Øyrehagen Sunde, published on the Storting’s Norwegian website in April 2024.

[1] Directly translated: “Magnus the Lawmender"

[2] Directly translated: “Law of the Land"

[3] The Constitutions of Melfi

[4] Bylov